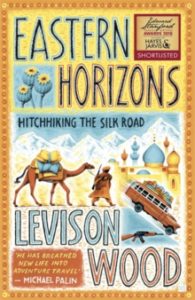

This interview in The Telegraph with traveler and author Levison Wood, excerpted from his book Eastern Horizons – Hitchhiking the Silk Road,will take you to magical places on his exploration of this mysterious planet:

This interview in The Telegraph with traveler and author Levison Wood, excerpted from his book Eastern Horizons – Hitchhiking the Silk Road,will take you to magical places on his exploration of this mysterious planet:

Those words, written in a letter, have resounded in my imagination ever since I first read them. Second Lieutenant James Whitehurst of the Royal Artillery has a lot to answer for.

It’s funny how small things can change your life in such big ways. Little was I to know when I lost my wallet at the age of 16, that it would have such a great influence on the rest of my life.

It was a pretty normal Saturday afternoon for a teenage boy from Staffordshire. We’d planned it for a while; the attractions of Alton Towers were too strong to resist and one day a few of us from school cycled the 14 miles through the Moorlands to try and sneak into the theme park. There was a little hole in the fence where we could climb in; and from there it was a simple case of avoiding the security guards with their big dogs and emerging out of the rhododendron bushes without any of the staff noticing. We all made it, and found ourselves dusting off twigs inside the castle grounds before lunch. Mission accomplished. Now we were at liberty to go on the rides and have a fun afternoon in the park without spending all of our pocket money on the entry ticket.

Karma got me back though when, an hour later, having enjoyed being hurled around on the Corkscrew roller coaster, I wobbled off, only to discover, much to my horror, that my wallet was gone. Had it fallen out? Perhaps it had been stolen. Either way, it was extremely annoying at the time and a severe blow to my finances, especially since my bus pass was in there and it would mean paying the full fare on the number seven to Cheadle.

Luckily for me, though, the wallet turned up in the post a week after I lost it. Surprisingly, it was complete with all of its contents, including the bus pass, and with it came a short letter from the man who’d found it. I was impressed by its style and politeness, and the way Second Lieutenant James Whitehurst of the Royal Artillery addressed me as an adult. It was on smart paper complete with an embossed watermark. He threw in, dryly, that he’d written it in the early hours of the morning, apologising if the writing was untidy – he was up at that time because, as an officer in the Army, he had very important duties to attend to. I pictured a dashing young soldier dug in a shell scrape on manoeuvres in some secret location, preparing his men for war.

Eager to find out more about my new hero, I wrote back immediately, thanking him for his integrity and having taken the time to write at all, when even the most honest of folk these days would have simply handed the wallet in to the local police station and let them deal with it. I’d been interested in a career in the Army ever since I was a kid, but nobody I knew had joined, especially as an officer, and I hadn’t the first clue how to go about applying, so, seeing the opportunity I asked if he wouldn’t mind offering me some tips.

The reply came by return of post in the form of six full pages of sound and practical advice: learn to read a map and a compass, get fit, run a mile and a half in nine minutes, join the TA, read the news, know your military history… take a gap year, and above all, travel.

There it was in black and white – a plan for the future, who’d have thought it? Determined on my new path, I set about following this advice to the letter for the next two years. Whilst finishing off my A-levels at school by day, at night I studied contours and ridgelines; went running and started doing press-ups, I read the broadsheets and tried my best to keep up to date with political scandal. I got stuck into history and read anything I could get my hands on. And, above all, I travelled.

I remember showing my parents the letter when I turned 18.

“Look, Dad, it says what I have to do right here, travel.”

“And what about university?” They didn’t seem too impressed and stared at me disapprovingly.

“I’ll go next year. I promise.”

With a few quid in my pocket and a brand-new rucksack, I set off alone. I was under no illusion that six months in Africa, Australia and south-east Asia was considered trail-blazing. I did, however, learn the basics of independent travel and the benefits of trying to understand other cultures, rather than staying put in isolated ghettos with other tourists. I found that one of the best ways to meet people was to hitchhike. It was generally unpredictable, often lonely, sometimes fun and frequently downright dangerous. But it was always interesting. Travel is by its very nature fascinating; an education. And I was eager to learn.

Much to my parents’ relief, on my return from my gap year, I enrolled at the University of Nottingham to continue my passion and study history. But all the way through university, I carried on travelling; each time, in an insatiable search of adventure, I would spend a month or two roaming the wilds, sometimes alone and sometimes in the company of a like-minded student.

I trekked through the highlands of Scotland and the plains of eastern Europe. Once, in a fit of juvenile irresponsibility, I even hitchhiked home from Cairo, by way of Jerusalem and Baghdad, in the middle of the Second Gulf War.

Mark Twain puts it nicely: “Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did… So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbour. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.”

The only times that my trade winds were disrupted were during the first two weeks of each summer holiday, when I would be obliged to complete a fortnight’s summer camp with the Officer Training Corps. I had enrolled in my first year of studies, following the advice of the letter I’d received three years before.

On one particularly wet soldierly day on the immense green slopes of Helvellyn, my thoughts turned to a book I’d stumbled across in the university library called The Great Game. Quite why I was reading that when the module I was supposed to be writing about was Frankish knights I don’t recall, but the distraction proved fortuitous. It told stories of bold young Englishmen sneaking over high mountain passes to defend the Empire, with India as its centrepiece, against brutish Russian marauders.

One person in particular stood out. I think I must have been impressed with the beard. Contemporary portraits show a barrel-chested man with immense facial fuzz and a turban that would have put the Ayatollah to shame. It belonged to Arthur Conolly, a dashing young officer in the British East India Company, who was the first person to coin the term “the Great Game”. One day, in the summer of 1839, he set off on an overland trip from England to India, to see if it was possible to travel along the Silk Road in the age of Empire. I suddenly had the urge to do the same.

I had already spent a very brief spell in the Indian subcontinent when I backpacked around the world before university, and it wasn’t a pleasant experience. I spent two weeks hiding in the mountains of Nepal in 2001, when the Nepali royal family was massacred in Kathmandu and the whole country went into lockdown. There were Maoist riots in the countryside and a nine o’clock curfew across the cities. People were getting shot in the streets and my passport had been stolen.

Luckily, I was taken in by a local farmer named Binod, who kept me away from the violence until things subsided. I finally retrieved my passport and embarked on a gruelling 53-hour bus journey to Delhi. In India, I got violently sick and had to fly home after only two days, having seen little more than the inside of my $2 hotel room – and the shared toilet.

Still, despite this, and perhaps because of it, I knew that I had to return to India. It has always been a part of the British consciousness. I thought back to childhood days of cricket in the park in Stoke-on-Trent, of being sent by my grandmother to the local corner shop, where I gazed in wonder at the rows of spices and exotic tins, with a smiling Bengali behind the counter. And, of course, there were my grandfather’s stories from the war – of docking in Calcutta, fighting the Japanese in Burma, and marching through thick, jungle-clad mountains alongside his Gurkha allies into Kohima.

Romantic notions of being on the road took hold, and in June the next year, with exams out of the way, I set off to hitchhike to India, wild and carefree, and thoroughly unprepared for my journey.

That summer was one of the best of my life. Time flew by in a hazy mixture of warm afternoons, snoozing in parks and staying with old friends. France was little more than a quick escape from the dingy dockyards of Calais, followed by shortcuts through vineyards in Champagne, but Germany passed by slowly and in vivid detail. The dream was suddenly a reality.

Red-tiled roofs jutted skyward and colourful flowers danced on the eves of half-wood, half-brick houses.

White carnations dangled in Teutonic uniformity from symmetrical hanging baskets on wooden balustrades and evenly mowed green lawns – all at the peak of their pride in midsummer. The thought of the Black Forest mountains with their emerald lakes still sends a shiver down my spine.

I travelled mostly at night and usually in the company of sullen lorry drivers. The stars would fade into the atmosphere as the dim light of dawn gradually approached, and it got wilder and more romantic as I went east. I was always delighted to be greeted with ever more attractive scenes of Swabian medievalism on entering a new town. I had breakfast in cobbled alleyways with the aroma of freshly baked pretzels, and lunches of Bratwurst, served by Bohemian girls with deep grey eyes. Days and weeks passed by. I hitched from town to town. Sleep would come rough, more often than not; next to rivers, hedgerows and even roundabouts. And when I became sick of the mosquitoes or slugs that were my constant bed partners, I would sometimes pay for the cheapest bed in a dormitory, but often find it worse. When the dorms became too loud, I would return to the streets or the parks, and disused factories.

I got to Estonia, where I dined with diplomats by day and slept on the ancient ramparts of the city walls by night. I would eat bread and soup at the National Library canteen, and write emails and letters to embassies trying to chase up my visas, and when I tired of that, I took the bus to the beach at Pirita, where the most beautiful girls in Europe gathered to bathe in the surprisingly warm Baltic Sea. I was an Englishman alone, before it became popular for stag parties, sitting in the beer gardens of the central Tallinn square, or overlooking the harbour from the upper town. I could have stayed for the rest of the summer and in fact almost two weeks passed by, hardly noticed.

But one beautiful afternoon, as I sat reading and drinking coffee, the realisation dawned on me that it was looking less likely that I would get any further.

“Your Iranian visa will be ready in Warsaw,” the officials said in Tallinn.

“Not here,” they said in Warsaw. “Try in Moscow.”

And as for a Russian visa: “Only in London,” they said. “You have to collect in person.”

It became more and more clear that no matter how many phone calls I made or letters I wrote, I would have to return to England to get the paperwork sorted.

I felt like a fraud and it was hard to hide my feelings of disappointment. But in the end, there was nothing to be done. The summer was coming to an end; the beach at Pirita was empty. I resolved to go home and start again as soon as I had obtained the necessary clearance. Next time I would be more thorough, I promised myself. Things weren’t so bad. Above all, at least I had travelled.

Eastern Horizons – Hitchhiking the Silk Road by Levison Wood is published by Hodder & Stoughton (£20). To order your copy for £16.99 plus p&p call 0844 871 1514 or visit books.telegraph.co.uk

Leave a Reply