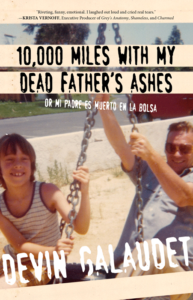

Funny story by author Devin Galaudet about traveling to Spain with his Dad in his suitcase. Here is an excerpt from his book 10,000 Miles With My Dead Father’s Ashes:

Funny story by author Devin Galaudet about traveling to Spain with his Dad in his suitcase. Here is an excerpt from his book 10,000 Miles With My Dead Father’s Ashes:

On the morning I arrived in Spain, I walked through the tall glass doors of my five-star hotel in Sevilla (press trips have their perks) and out into a springtime breeze. I carried a paper map from the concierge and my blue backpack with Dad in it. It was an organic decision to take Dad for a stroll. He had been cooped up in my luggage and I began to feel badly about it, but I did not completely understand why. However, once I slung him over my shoulder and felt his pull against my back, it just felt right. Better than that, I stood taller knowing I carried around my dead father.

Don’t mind us, I thought. It is just me and my dead father out for a stroll. Don’t mess with me, or I will swing my dead father over my head and beat you senseless with him. The idiocy and irony of it all amused me for hours. Secretly, I prayed that curious strangers would ask what was in the backpack.

Together we walked through the 15th- and 16th-century archways, cathedrals, and plazas and soaked up the sights. I smelled the sugar from the bakery and the freshly brewed coffee. I watched hip Spaniards, who took sips and nibbled as they hurried along crowded streets wearing freshly ironed suits and dresses. All the guys had slicked-back hair and overly worked style—a friend from Madrid would later describe the men as señoritos. All the women wore formfitting dresses and aloof expressions. The city was a metrosexual’s paradise of parading beautiful people in mysterious dark sunglasses. I turned my head to watch every woman who passed. Every man, too. Every person I saw looked tanned and done up in tailored clothes. I must have appeared homeless.

I brought one carry-on suitcase and a small backpack for Dad. Socks, shirts, and underwear I washed in the sink of my hotel, because I owned no other suitcase and could not justify placing Dad into checked baggage. I also feared that a lack of cabin pressure might make the plastic drum where Dad resided explode in the belly of the airplane. So Dad took up most of the suitcase.

I passed cops and store owners who had character and paunchiness, who appeared to play supporting cast for all the attractive people. They were older. They leaned in doorways, on the many cars parked along the street, or on the long handle of a push broom. They waited on park benches, chatted to each other, and listened to the world at a much slower pace, without a care at all. They acted almost in opposition to the racing of the youth, who pirouetted around them. I pretended some of them eyed me, the stranger and his rucksack, which gave me warm guilty feelings as I doubted Dad had ever seen a place like this. I decided within a few hours that Dad’s many lies helped me visit Spain. Briefly, I was grateful.

“Don’t mind us, I thought. It is just me and my dead father out for a stroll. Don’t mess with me, or I will swing my dead father over my head and beat you senseless with him.”

“So, why do you think now is the time for opera in Seville?” I said from the second row of a small press conference in a small white room around a long table. It was a lame question. One of many I asked over the hour. I learned early on that much of the question-asking is part of a larger dog-and-pony show.

Dad sat between my feet in my backpack with one of its straps wrapped around my leg, in case anyone burst into the room to rob me. Since Dad didn’t fit into the hotel room’s safe, I didn’t want to leave him in the room. So off to work we went.

The four photographers stood behind us, the seated journalists. Incessantly, they clicked and flashed with big digital single-lens reflex cameras, jockeying for the best camera angle to shoot the producer, a wide, bald guy who wore sunglasses and one of those tan vests with a dozen pockets over a pink dress shirt—a look that said, “I’m in the biz,” but just in Spanish.

The event went well. In general, producers want international media to ask lots of questions and help create the illusion of importance. They want photographers to take pictures of gathered media to get buzz. And I sat at the end of the table and wore translation headsets and asked questions and took notes and continued to feel like a fraud. To be fair to my old self, usurping a press trip to scatter Dad’s ashes for free was quite a coup. An act I am certain Dad would have appreciated.

I genuinely wanted Spain to get its money’s worth. “Over the next five years, how do you see the opera showcase progressing?” I said. The bald producer squirmed in his seat, put a hand to his jaw, and looked up at the ceiling. I sat poised with my pen pressed against my notepad.

“Hopefully, we will keep telling stories that matter, because we are passionate about what we do. We are passionate about life,” he said. Then he leaned back in his chair and looked satisfied and certain.

At the end of the day, which had brought similar press events, I took back to the street with Dad. I was in Spain with him draped across my shoulder, not out of love but out of obligation. I was not passionate about what I was doing and not passionate about life. I wanted to tell people that I had not only rescued him from an eternity of being in St. George but that I showed him Spain and made his final wish come true. I held him loosely by the strap as he dangled from one shoulder. I dared any thief in sight to just grab him and run.

Fulfilling his last wish made me feel like I was an idiot. I lied, if only through omission, to Spain, for what? So his wife could feel like the mission was accomplished? His nonsense story about returning home could be validated? If the situation were reversed, I would have sat forever on a shelf. He was a jerk even in death. Maybe I felt like an idiot because part of me still idolized him. And still, there I was, running around with a bag of dirt strapped to my back. We headed unconsciously down to Sevilla’s bullfighting ring. The iconic stadium wreaked of old-world-ness with its whitewashed, hand-plastered walls. Instinctively, I bought two tickets from a gold-toothed crone, one for myself and one for Dad, for later that night. I figured I owed Dad a guy’s afternoon out and wanted to see the fights, like old times. It was the closest thing I could get to the old Olympic Auditorium, and I needed inspiration.

Dad and I had gone to the Olympic when I was young. Before each visit, I grabbed Dad’s arm and dragged him down the hall and into my room. There among the old plates of food and game pieces littered on the floor was an old black-and-white television with tinfoil wrapped around the antenna. I pointed at the television as the Los Angeles Thunderbirds skated or Victor Rivera and the Twin Devils wrestled or Danny “Little Red” Lopez punched. I looked up at Dad, still holding his arm, and hoped his excitement matched my own. His approval, at the time, was all I ever wanted. He feigned enough interest for occasional tickets.

The Olympic was an icon for blue-collar entertainment in Los Angeles in the 1970s and aired boxing, wrestling, and roller derby on the old UHF channel 52. The building was falling apart, dingy, noisy, and had a slimy layer of grease, peanut shells, fake popcorn butter, and beer covering the floors and seats. Crowds rarely filled the place, but the audiences made up for it with loudness. Dad and I were surrounded by the cheering in Spanish and broken English from the downtown Angelenos. Beer splashed across us as wax-paper cups were thrown at the ring, and fights broke out in the rows behind us. Fights broke out in front of us. Fights broke out in the ring and on the track. That was our guy’s night out, which was more important than the results of the bouts.

I knew most of the outcomes were prearranged but hoped I was wrong. Not that it mattered. Dad leaned back and swirled his cerveza against the ridiculousness of it all and kept me well stocked with peanuts. He never cared for sports the way I did, but I felt him stare down at me, watching me engrossed in every moment. When there was a break in the action, I would look up at him just to see if he was paying attention to the games. He was not. He was always just watching me. He occasionally wiped a beer-foam mustache across my upper lip.

“I wanted to tell people that I had not only rescued him from an eternity of being in St. George but that I showed him Spain and made his final wish come true.”

The last time we visited the Olympic I was 16. I had seen an ad that wrestling was returning there after a several-year hiatus. We arrived ten minutes before the start and got first-row seats. The room was cavernous and populated by a few families with a few kids chasing each other around the ring.

By the time the show started, there were 50 people in the theater built to hold thousands. The ring was lit up with spotlights, and I was giddy again with the nostalgia of hanging around with Dad. The bags under his eyes were heavier, his face more worn, but he was still my dad.

The main event consisted of four bodybuilders and 14 fat guys who made up the battle royale, where 18 men slammed into each other over the vague ideal of good-versus-evil supremacy and one ultimate victor. At one point, one of the wrestlers was watching alongside of us. The guy was huge, rippling muscles, veins popping out of his arms and neck, covered in intimidating tattoos, wore a Mohawk, and he stood there with Dad.

Dad struck up a conversation with him. “So why aren’t you in there? Aren’t you supposed to kick ass or something?”

“For this crowd?” the wrestler said, waving a hand to shoo away the idea. Dad then threw his arm around the guy like he had known him for ages and even tried to get him in a headlock. They both laughed. I shuddered and took a step back. If I remember correctly, the wrestler’s schtick was bending a steel bar around his head. After they separated, Dad poked his new brawny friend in the chest like old wrestling interviews. I thought the guy was going to throw Dad in the ring and kill him. Instead they talked, without me, until after the light went back on in the auditorium and the final bits of the tiny crowd went home.

With a few hours to kill and bullfighting tickets in my pocket, I took Dad out on the town. He sat on the café table while I sipped an espresso outside in the sun. “So what do you think?” I said quietly to my backpack with Dad in it. “So this is it. You’re in Spain, you fucking jerk.”

While he was alive, I think I swore at him once. Now that he was dead, I granted myself the privilege with abandon. The oddness of talking to the sack would grate at me and felt embarrassing, but I wanted this trip to be memorable for him. As I leaned back and sipped, I described the black-veiled religious ladies with their lacy hoop skirts, weathered cigar-smoking men playing chess in the park, youthful hipster couples holding hands, and other charming clichés that embodied southern Spain. I would eventually learn to embrace our one-sided chats, but in the beginning, I felt phony and manipulated. I was carrying on a charade for my own benefit, although there seemed to be a purpose to all the talking and description. A deep part of me wanted to make up for lost time. I spent the next hour trying to create a world where I spoke and Dad listened.

__________________________________

From 10,000 Miles With My Dead Father’s Ashes. Courtesy of Rare Bird Books. Copyright © 2018 by Devin Galaudet.

Leave a Reply