Although our ability to easily pick up a new skill declines with age, harnessing a specific type of mindset can help you learn effectively as an adult.

Tom Vanderbilt’s fascination with the process of life-long learning began with his daughter’s hobbies: piano, soccer, Tae Kwon Do. He wanted to encourage her new pursuits, and accompanied her to the lessons or tournaments. As she exercised her mind, he would answer emails, play with his phone or stare into space until his daughter had finished.

He soon recognised the hypocrisy of the situation. “I was impressing upon her the importance of having a broad education in all these different skills,” he says. “But she might have easily asked me, ‘Well, why don’t you do all these things then?’”

Starting with chess lessons, he decided to spend a year pursuing a range of new skills himself. He learnt to sing, draw, juggle and surf. At no point did he hope to fully master the abilities or to show off his prowess with an extraordinary feat, such as winning American Idol.

“As adults, we instantly put pressure on ourselves with goals,” he says. “We feel like we don’t have the luxury to engage in learning for learning’s sake.” Instead, he wanted to revel in the pleasure of the process.

Vanderbilt details his journey in his January 2021 book Beginners, which combines his own personal revelations with the cutting-edge science of skill acquisition. Keen to find out more, we discussed the myths of adult learning, and the substantial benefits that the “beginner’s mindset” can bring to our lives.

How to learn well

Beginning the project in his late 40s, Vanderbilt knew that he would struggle to match the learning abilities of children like his daughter. Children are especially good at picking up patterns implicitly – understanding that certain actions will lead to certain kinds of events, without any explanation or description of what they are doing. After the age of 12, however, we lose some of that capacity to absorb new information.

Young children are wired to learn – but that doesn’t mean adults can’t (Credit: Alamy)

We shouldn’t be too pessimistic about our own abilities, though. While adults may not absorb new skills as readily as a child, we still have “neuroplasticity” – the ability for the brain to rewire itself in response to new challenges. In his year of learning, Vanderbilt met many people, long past middle age, who were still exercising that “superpower”.

What’s more, Vanderbilt’s research revealed some basic principles of good learning that anyone can use to make our learning more effective. The first may seem obvious but is easily forgotten: we need to learn from our mistakes. So, rather than just mindlessly repeating the same actions over and over, we need to be more focused and analytical, thinking about what we did right and what we did wrong. (Psychologists call this “deliberate practice”.) Vanderbilt noted this with chess playing. You could put in the hours with hundreds of online games, but that was not going to be as effective as studying the strategies of professionals or discussing the reasons for your losses with a chess teacher.

A second principle is more counter-intuitive: we need to make sure that our practice is varied. When juggling, for example, it helped to switch the objects, or to change how high you throw them; he tried it sitting down, and while walking. As one scientist told Vanderbilt, this is “repetition without repetition” and it forces the brain’s learned patterns to become more flexible, allowing you to cope with the unpredictable difficulties – such as a mistake in one of your earlier movements that could lead you to lose control.

While you may find it helpful to observe true experts executing a skill it can also be useful to watch other novices

Even more intriguingly, Vanderbilt discovered that we often learn best when we know that we will have to teach others the same skill. It’s not clear why this is, but that expectation seems to increase people’s interest and curiosity, which primes the brain’s attention and helps ensure that it lays down stronger memory traces. (Vanderbilt had lots of opportunities to teach what he had learnt, since he often included his daughter in his projects.) So, whatever you are personally trying to master, consider sharing that skill with someone you know. And while you may find it helpful to observe true experts executing a skill, Vanderbilt found that it can also be useful to watch other novices, since you can more easily analyse what they are doing right and what they are doing wrong.

With this knowledge, Vanderbilt made good progress with each of the skills that he set out to learn. Singing, he says, offered one of the biggest hurdles, emotionally. “It was this process of opening oneself up to a stranger in the most raw way,” he says. When he had overcome those nerves, however, it also proved to be the most rewarding. “It is the thing I probably took to the most, because it has such an inherent pleasure and makes you feel so good.” He eventually became a member of New York’s Britpop Choir.

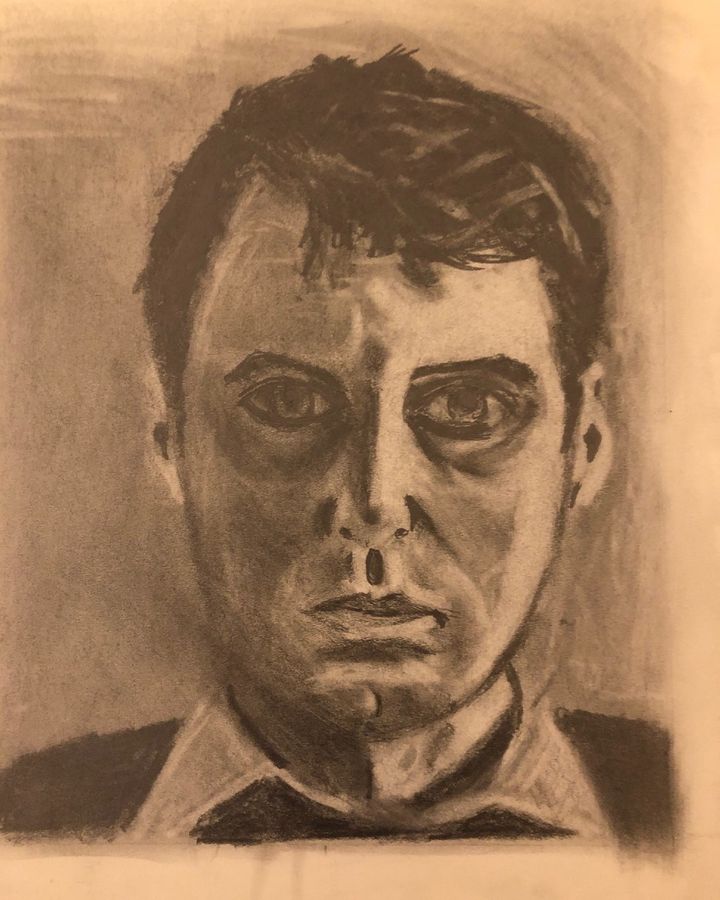

If you are inspired to take up a new pastime yourself, Vanderbilt advises starting out with something that is easy to integrate into your existing lifestyle. You may be surprised by the speed of your progress, he says. “A lot of people get hung up on the idea that this is just a massive time investment – that there’s no end of the road – and that’s very daunting to them.” He found that his drawing, for example, had improved significantly in the time that it would normally take to binge-watch a TV boxset.

The why factor

You may still wonder why you should make the effort, when you could be vegging out on your sofa.

Tom Vanderbilt says improving his drawing required less investment of time than he had imagined (Credit: Tom Vanderbilt)

But Vanderbilt points out that there are many general benefits to embracing any new skill – including some long-term brain changes that could offset some of the mental decline that often comes with ageing. Vanderbilt points to one study of adults – aged 58 to 86 – who pursed a handful of courses in subjects like Spanish, music, composition and painting. After a few months, they had not only made good progress in the individual skills, but also showed a pronounced improvement on more general cognitive tests – matching the performance of adults who were 30 years younger.

Intriguingly, the benefits here seemed to come from trying out multiple skills, rather than focusing exclusively on one particular expertise. As Vanderbilt writes in his book: “Rather than grinding out a marathon, you are putting your brain through a variety of high-intensity interval workouts. Each time you begin to learn that new skill, you’re reshaping. You’re training your brain again to be more efficient.” We tend to see the ‘dilettante’ as someone who is superficial and lacks dedication. But it seems that the jack of all trades – the perpetual beginner – may have a sharper brain than the master of one single ability.

The lifelong pursuit of many different interests may even increase your creativity. As David Epstein also noted in his book Range, Nobel laureates were many times more likely to have enjoyed artistic pursuits such as music, dance, visual art or creative writing than other scientists.

It seems that the jack of all trades – the perpetual beginner – may have a sharper brain than the master of one single ability

As you set about learning a new skill, there will be frustrations and moments of failure – but these may in fact be the most important experiences of the whole process. After years of experience in journalism, Vanderbilt says that the new challenges were a welcome change to his “professional complacency”. “It sort of opened my mind and brought me back to this sense of not knowing,” he says. This was especially true for the skills – such as drawing – that already felt somewhat familiar. “The learning of the thing itself was often different from what I imagined. My expectations were constantly being upset.”

Abundant research has shown that intellectual humility – the capacity to recognise the limits of our knowledge – can powerfully improve our thinking and decision making. And that capacity to reconsider our preconceptions and open our minds to new ways of thinking may be increasingly important in today’s rapidly changing world. Whether we are learning for pleasure or attempting to boost our professional skills, we could all do well to cultivate that “beginners’ mindset”, where nothing is certain, and there is everything to learn.

Tom Vanderbilt’s book Beginners: The Joy and Transformative Power of Lifelong Learning (Atlantic Books/Knopf) was published in January.

David Robson is the is author of The Intelligence Trap: Why Smart People Do Dumb Things

Leave a Reply