I love music and attend live music concerts in small clubs and SFJazz several times a week. This passion has followed me my entire life. While at a San Francisco club in 1976 dancing to the flaming Zydeco sounds of Clifton Chenier by myself, I met a Cajun man who was a powerful dancer. Lloyd was from New Orleans. By the time the club closed and the sun rose on Ocean Beach, we had talked ourselves silly whiling eating leftover barbequed ribs. As we tossed the bones out his truck window to the screeching gulls, Lloyd invited me the Big Easy to be his assistant at the annual New Orlean’s Jazz Festival. Couldn’t say no to that!

The Jazz Fest was the epicenter of hot hot hot music and I was assigned to drive the musicians around town and to their gigs. This included Louis Armstrong’s band members. Along with schmoozing with the greats, I got to dance and stomp and be in awe of their talent while bopping around backstage. This was a volunteer gig that I continued for 9 years in a row. Divine. The story “Two Steppin’ & Pussy Poppin” is about this experience and included in my latest book Dance Life: Movin’ & Groovin’ Around the Globe.

Louis was a jolly and pleasant man with a deep laugh. I had not idea his life had been so difficult until I read this story excerpted from his memoir Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans. What a survivor! May we all be so resilient.

Louis Armstrong Remembers How He Survived the 1918 Flu Epidemic in New Orleans

Written by Josh Jones. Published in Open Culture.

Born into poverty in New Orleans in 1901, and growing up during some of the most brutal years of segregation in the South, Louis Armstrong first lived with his grandmother, next in a “Colored Waif’s Home” after dropping out of school at age 11, then with his mother and sister in a home so small they had to sleep in the same bed. After already living through the first World War, he would go on to witness the Spanish Flu epidemic, the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, and the turbulent 1960s and the Vietnam conflict.

That’s a lot for one lifetime, though for much of it, Armstrong was a star and living legend who beat the odds and rose above his origins with will and talent. Even so, he suffered some severe ups and downs during the hard times, touring so much to cover his debts in the lean 1930s, for example, that he injured his lips and fingers, and finally moving to Europe when the mob came after him.

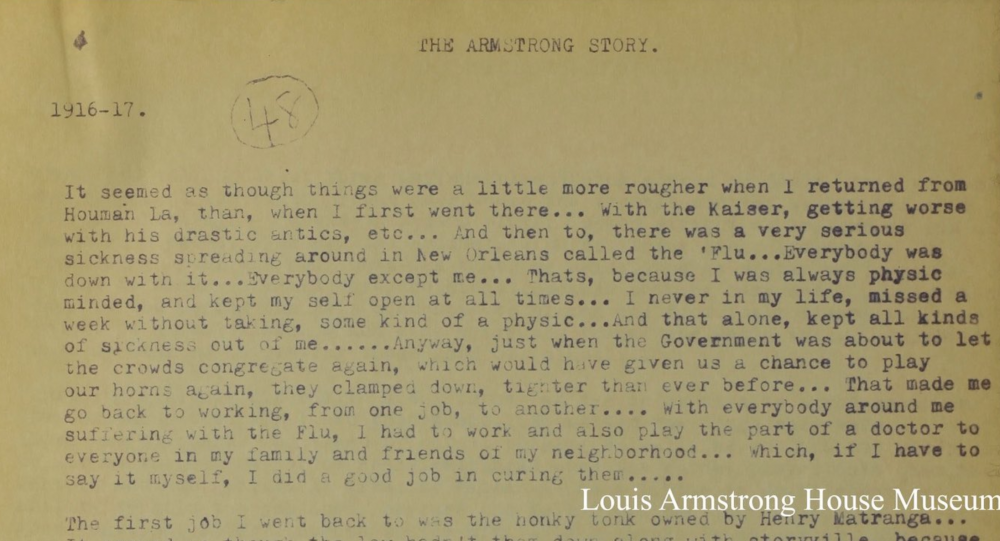

Armstrong’s descriptions of his experience of the 1918 influenza pandemic—as he remembers it in his 1954 memoir Satchmo: My Life in New Orleans—are almost jaunty, as you can partly see in the typescript page above from the Louis Armstrong House. But he remembered it from the perspective of a 17-year-old musician in robust health—who seemed to have some kind of resistance to the flu.

He devotes no more than two paragraphs to the flu, which hit the city hard in October of that year. According to the Influenza Encyclopedia, an online project documenting the flu in the U.S. between 1918-1919, New Orleans city authorities “acted immediately,” once they discovered the outbreak, arrived by cargo ship the month before.

On October 9th, the New Orleans Superintendent of Health, “with Mayor Martine Behrman’s consent and the blessing of state authorities… ordered closed all schools (public, private, and parochial, as well as commercial colleges), churches, theaters, movie houses, and other places of amusement, and [prohibited] public gatherings such as sporting events and public funerals and weddings.”

For a struggling young musician making a living playing clubs and riverboats, the closure of “other places of amusement” took a serious toll. The loss of livelihood is what seems to have hurt Armstrong the most when he returned to the city from touring, still unsure if the Great War would end.

When I came back from Houma things were much tougher. The Kaiser’s monkey business was getting worse, and, what is more, a serious flu epidemic had hit New Orleans. Everybody was down with it, except me. That was because I was physic-minded. I never missed a week without a physic, and that kept all kinds of sickness out of me.

Whatever “physic” helped Armstrong’s avoid infection, it wasn’t for lack of exposure. In lieu of playing the trumpet he began caring for the sick, since all of the hospitals, even those that would take black patients, were completely overcrowded.

Just when the government was about to let crowds of people congregate again so that we could play our horns once more the lid was clamped down tighter than ever. That forced me to take any odd jobs I could get. With everybody suffering from the flu, I had to work and play the doctor to everyone in my family as well as all my friends in the neighborhood. If I do say so, I did a good job curing them.

We might imagine some of those “odd jobs” were what we now call “essential”—i.e. low paid and high risk under the circumstances. He persevered and finally got a gig playing a “honky-tonk” that avoided a shut-down because it was “third rate,” and he “could play a lot of blues for cheap prostitutes and hustlers.” Few things could get Satchmo down, it seemed, not even a flu pandemic, but he was one of the lucky ones—luckily for the future of jazz. Only, we don’t have to imagine how hard this must have been for him. We just have to take a look around.

Learn more about the 1918 influenza epidemic in the U.S. at the Influenza Encyclopedia and read the rest of Armstrong’s account of his formative years at the Internet Archive.

Related Content:

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC.

Leave a Reply