The color blue has a history and surrounds us in our daily life. But how often do you look at the sea or sky or eyes to try and capture their unique shades and hues? This story is about the enchantment of blue…

I took this photo in Moulay Idris, Morocco—a land of many shades of blue.

Long ago, I slept spontaneously for several days on a duney beach at the tip of the island of Formentera. It is the smallest of Spain’s Balearic islands in the Mediterranean Sea. I was escaping my madcap dance adventure on the jetsetter island of Ibiza. Hence, I hopped on the ferry—not knowing its destination—debarked and rented a moped. A glass of Tempranillo, a Zarzuela de Mariscos, and lengthy banter in Spanish with other vagabonders at a port-side cafe kept me captive until night fell. I followed a road to the very tip of the island and made myself at home under the stars serenaded by the lapping waves.

I lay on the sand, wrapped in a sarong and sweater, huddled against the dune grass for warmth—I had not brought a sleeping bag. As the sun rose, I was struck by the dazzling blueness of the sparkling sea. How many ways could I describe the color in order to really absorb and memorize the magnificence of this scene?

Here are my journal notes from that languid day on the Spanish sand. Also included below are an encouragement to try this writing exercise AND an article in My Modern Met titled “The History of the Color Blue: From Ancient Egypt to the Latest Scientific Discoveries.”

Travel Journal Notes on Blue in 1992

I awake and see the blue water heaven glittering beyond my sand dune nest. I’m perched on rosy sandstone cliffs at the edge of Formentera— hanging over a blue ocean that stretches out past sunrises and sunsets. How to describe this blue? Perhaps…

Mediterranean blue—deep yet translucent. Aquamarines and sapphires thrown into a watery heap. Inspiring ocean blue. Diveable blue. Celestial blue. Deep sea blue. Drowning blue. Angelic blue. Truthful blue. Blue as my deepest, most peaceful feelings. Electric currents of blue. Bluebird tapestry blue.

![]()

Try this writing exercise to stimulate new descriptions that add a specific sensuality to the scene. A sunset, a field of wheat, a bowl of fruit— stare at it and let the colors speak to you. Then jot down words and a narrative that opens up your vision and descriptive powers beyond plain ole “blue.”

![]()

Here is a super informative article published in My Modern Met on the origins of blue:

The History of the Color Blue: From Ancient Egypt to the Latest Scientific Discoveries

The color blue is associated with two of Earth’s greatest natural features: the sky and the ocean. But that wasn’t always the case. Some scientists believe that the earliest humans were actually colorblind and could only recognize black, white, red, and only later yellow and green. As a result, early humans with no concept of the color blue simply had no words to describe it. This is even reflected in ancient literature, such as Homer’s Odyssey, that describes the ocean as a “wine-red sea.”

Blue was first produced by the ancient Egyptians who figured out how to create a permanent pigment that they used for decorative arts. The color blue continued to evolve for the next 6,000 years, and certain pigments were even used by the world’s master artists to create some of the most famous works of art. Today it continues to evolve, with the latest shade discovered less than a decade ago. Read on to learn more about the color’s fascinating history.

Egyptian Blue

Egyptian Juglet, ca. 1750–1640 B.C. (Photo: Met Museum, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift)

There’s a long list of things we can thank the ancient Egyptians for inventing, and one of them is the color blue. Considered to be the first ever synthetically produced color pigment, Egyptian blue (also known as cuprorivaite) was created around 2,200 B.C. It was made from ground limestone mixed with sand and a copper-containing mineral, such as azurite or malachite, which was then heated between 1470 and 1650°F. The result was an opaque blue glass which then had to be crushed and combined with thickening agents such as egg whites to create a long-lasting paint or glaze.

The Egyptians held the hue in very high regard and used it to paint ceramics, statues, and even to decorate the tombs of the pharaohs. The color remained popular throughout the Roman Empire and was used until the end of the Greco-Roman period (332 BC–395 AD), when new methods of color production started to evolve.

Figure of a Lion. ca. 1981–1640 B.C. (Photo: Met Museum, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift)

Fun fact: In 2006, scientists discovered that Egyptian blue glows under fluorescent lights, indicating that the pigment emits infrared radiation. This discovery has made it a lot easier for historians to identify the color on ancient artifacts, even when it’s not visible to the naked eye.

Ultramarine

“Virgin and Child with Female Saints” by Gérard David, 1500. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The history of ultramarine began around 6,000 years ago when the vibrant, semi-precious gemstone it was made from—lapis lazuli—began to be imported by the Egyptians from the mountains of Afghanistan. However, the Egyptians tried and failed to turn it into a paint, with each attempt resulting in a dull gray. Instead, they used it to make jewelry and headdresses.

Also known as “true blue,” lapis lazuli first appeared as a pigment in the 6th century and was used in Buddhist paintings in Bamiyan, Afghanistan. It was renamed ultramarine—in Latin: ultramarinus, meaning “beyond the sea”—when the pigment was imported into Europe by Italian traders during the 14th and 15th centuries. Its deep, royal blue quality meant that was highly sought after among artists living in Medieval Europe. However, in order to use it you had to be wealthy, as it was considered to be just as precious as gold.

“Girl with a Pearl Earring” by Johannes Vermeer, circa 1665. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Ultramarine was usually reserved for only the most important commissions, such as the blue robes of the Virgin Mary in Gérard David’s Virgin and Child with Female Saints. Supposedly, Baroque master Johannes Vermeer—who painted Girl with a Pearl Earring—loved the color so much that he pushed his family into debt. It remained extremely expensive until a synthetic ultramarine was invented in 1826, by a French chemist, which was then aptly named “French Ultramarine.”

Fun fact: Art historians believe that Michelangelo left his painting The Entombment (1500–01) unfinished because he could not afford to buy more ultramarine blue.

Cobalt blue

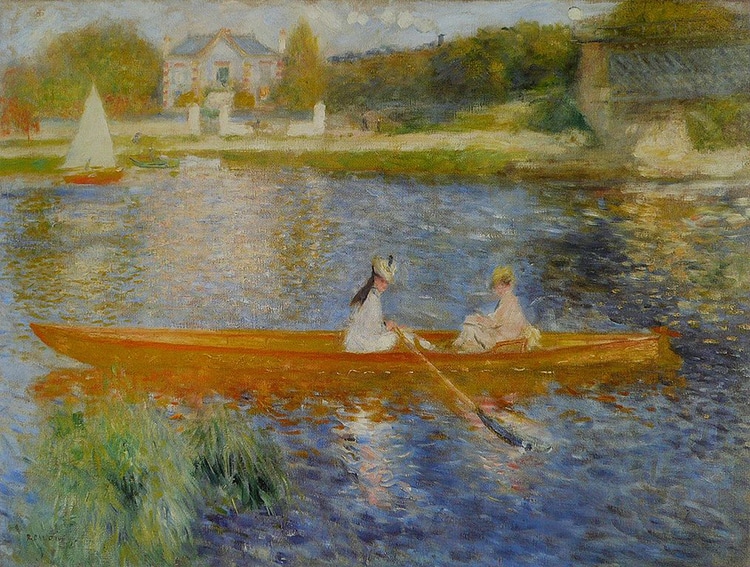

“The Skiff (La Yole)” by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, 1875. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Cobalt blue dates back to the 8th and 9th centuries, and was then used to color ceramics and jewelry. This was especially the case in China, where it was used in distinctive blue and white patterned porcelain. A purer alumina-based version was later discovered by French chemist Louis Jacques Thénard in 1802, and commercial production began in France in 1807. Painters—such as J. M. W. Turner, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Vincent Van Gogh—started using the new pigment as an alternative to expensive ultramarine.

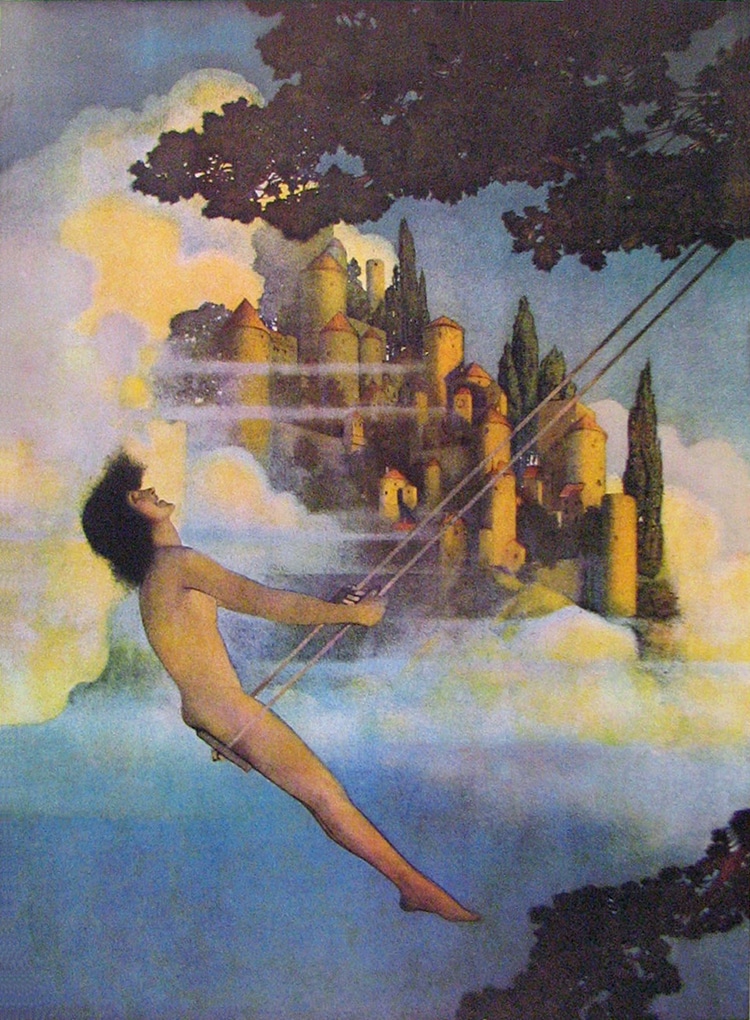

“Dinky Bird” by Maxfield Parrish, 1904. Via Wikimedia Commons

Fun fact: Cobalt blue is sometimes called Parrish blue because artist Maxfield Parrish used it to create his distinct, intensely blue skyscapes.

Cerulean

“Summer’s Day” by Berthe Morisot, 1879. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Originally composed of cobalt magnesium stannate, the sky-colored cerulean blue was perfected by Andreas Höpfner in Germany in 1805 by roasting cobalt and tin oxides. However, the color was not available as an artistic pigment until 1860 when it was sold by Rowney and Companyunder the name of coeruleum. Artist Berthe Morisot used cerulean along with ultramarine and cobalt blue to paint the blue coat of the woman in A Summer’s Day, 1887.

Fun fact: In 1999, Pantone released a press release declaring cerulean as the “Color of the Millennium,” and “the hue of the future.”

Indigo

Indigo, historical dye collection of the Technical University of Dresden, Germany. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Although blue was expensive to use in paintings, it was much cheaper to use for dying textiles. Unlike the rarity of lapis lazuli, the arrival of a new blue dye called “indigo” came from a excessively grown crop—called Indigofera tinctoria—that was produced across the world. Its import shook up the European textile trade in the 16th century, and catalyzed trade wars between Europe and America.

Indigo dyed textile (England), 1790s. (Photo: Matt Flynn via Wikimedia Commons)

The use of indigo for dyeing textiles was most popular in England, and was used to dye clothing worn by men and women of all social backgrounds. Natural indigo was replaced in 1880, when synthetic indigo was developed. This pigment is still used today to dye blue jeans. However, over the last decade scientists have discovered that the bacteria Escherichia coli can be bio-engineered to produce the same chemical reaction that makes indigo in plants. This method, called “bio-indigo,” will likely play a big part in manufacturing environmentally friendly denim in the future.

Fun fact: Sir Isaac Newton—the inventor of the “color spectrum”—believed that the rainbow should consist of seven distinct colors to match the seven days of the week, the seven known planets, and the seven notes in the musical scale. Newton championed indigo, along with orange, even though many other contemporary scientists believed the rainbow only had five colors.

Navy blue

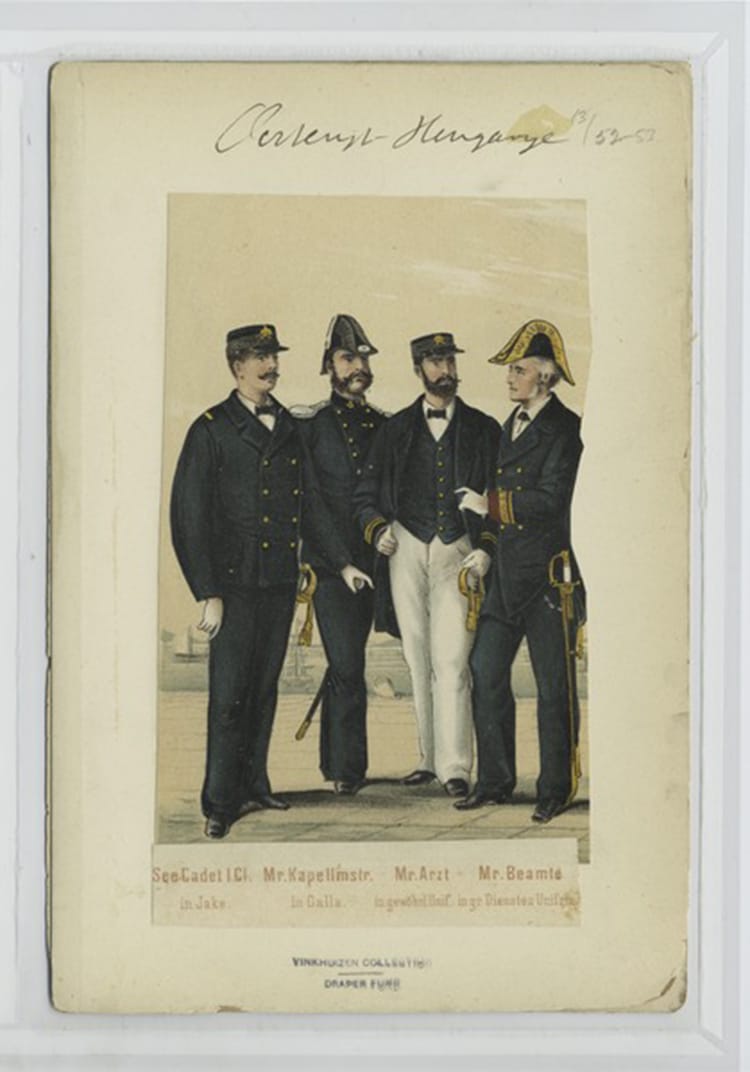

Navy cadets in uniform, 1877. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Formally known as marine blue, the darkest shade of blue—also known as navy blue—was adopted as the official color for British Royal Navy uniforms, and was worn by officers and sailors from 1748. Modern navies have since darkened the color of their uniforms to almost black in an attempt to avoid fading. Indigo dye was the basis for historical navy blue colors dating from the 18th century.

Fun fact: There are many variations of navy blue, including Space cadet, a color that was formulated in 2007. This hue is associated with the uniforms of cadets in the space navy; a fictional military service armed with the task of exploring outer space.

Prussian blue

“The Great Wave off Kanagawa” by Katsushika Hokusai, 1831. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Also known as Berliner Blau, Prussian blue was discovered accidentally by German dye-maker Johann Jacob Diesbach. In fact, Diesbach was working on creating a new red, however, one of his materials—potash—had come into contact with animal blood. Instead of making the pigment even more red like you might expect, the animal blood created a surprising chemical reaction, resulting in a vibrant blue.

Prussian blue pigment. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Pablo Picasso used the Prussian blue pigment exclusively during his Blue Period, and Japanese woodblock artist Katsushika Hokusai used it to create his iconic The Great Wave off Kanagawa, as well as other prints in his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series. However, the pigment wasn’t only used for creating masterpieces. In 1842, English astronomer Sir John Herschel discovered that Prussian blue had a unique sensitivity to light, and was the perfect hue to create copies of drawings. This discovery proved invaluable to the likes of architects, who could create copies of their plans and designs, that are today known as “blueprints.”

Fun fact: Today, Prussian blue is used in a pill form to cure metal poisoning.

International Klein Blue

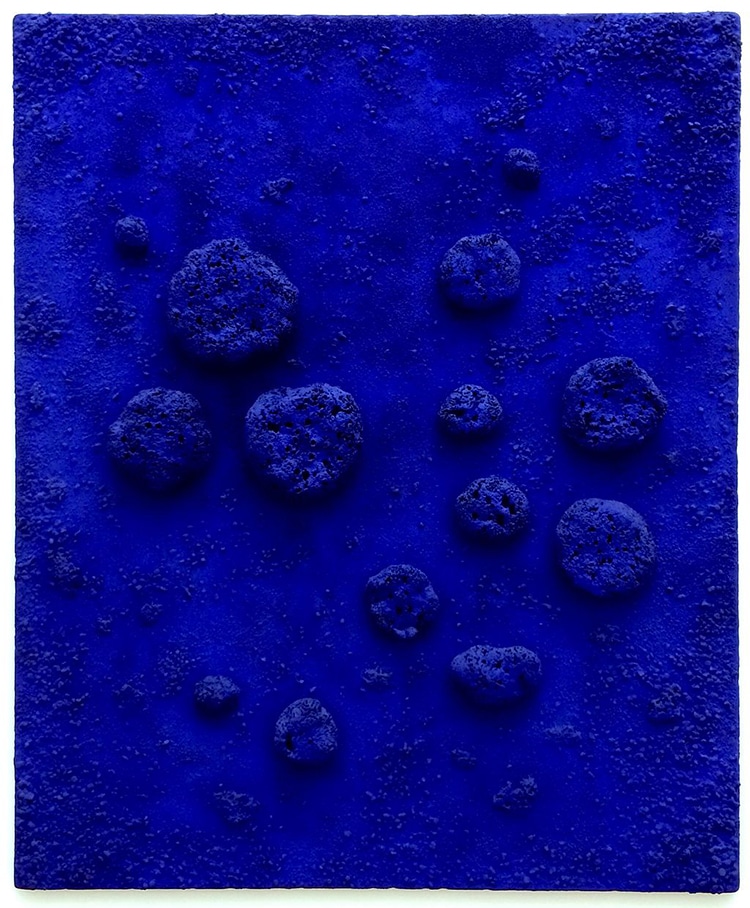

“L’accord bleu (RE 10)”, 1960 by Yves Klein. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

“IKB 191”, 1962 by Yves Klein. (Photo: Christophe Brocas via Flickr)

In pursuit of the color of the sky, French artist Yves Klein developed a matte version of ultramarine that he considered the best blue of all. He registered International Klein Blue (IKB) as a trademark and the deep hue became his signature between 1947 and 1957. He painted over 200 monochrome canvases, sculptures, and even painted human models in the IKB color so they could “print” their bodies onto canvas.

Fun fact: Klein once said “blue has no dimensions. It is beyond dimensions,” believing that it could take the viewer outside the canvas itself.

The Latest Discovery: YInMn

YInMn Blue. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

In 2009, a new shade of blue was accidentally discovered by Professor Mas Subramanian and his then graduate student Andrew E. Smith at Oregon State University. While exploring new materials for making electronics, Smith discovered that one of his samples turned bright blue when heated. Named YInMn blue, after its chemical makeup of yttrium, indium, and manganese, they released the pigment for commercial use in June 2016.

Fun fact: YInMn blue was recently added to the Crayola crayon collection.

Leave a Reply