This is an empowerment mom story. Maybe we don’t want our sons and daughters to teach us how to climb a vertical granite face—we probably don’t even want them climbing it! But this mom is different and so is her kid—Alex Honnold—the awesome climber in the teeth-clenching movie Free Solo in which he attempts to become the first person to ever free solo climb El Capitan in Yosemite.

What a relief that at the premier showing at the Mill Valley Film Festival last year, at the end of the film he stood up and bowed. He was in the audience and this meant he did not die. The entire audience let out a collective exhale that washed over the theater. Phew! I can only imagine how his mother felt during these attempts.

Now it is her turn to make us nervous. Dierdre Wolownick took up climbing at age 57 in a gym. Ten months later, with the guidance of her son, she climbed Half Dome. At 66 Dierdre did the Big One (El Cap), again with her son’s coaching—and she wrote a book about it.

Read her foray into climbing and her insights into the mother-son relationship in this REI Co-Op Journal story:

DIERDRE WOLOWNICK ON BEING THE OLDEST WOMAN TO CLIMB EL CAPITAN—AND ALSO ALEX HONNOLD’S MOM

In her new book, Wolownick shares her story of adventure and resilience—both on and off the rock.

You could read The Sharp End of Life: A Mother’s Story by Dierdre Wolownick to find out what it’s like to climb El Capitan in Yosemite National Park at age 66—being the oldest woman on record to do so—or to find out what it’s like to be Alex Honnold’s mom, hearing after the fact (later that morning) that he’d made history free soloing El Capitan. But in Wolownick’s writing, you’ll get a deeper, more reflective dive than that. Her intimate memoir is a story of the tricky cards that life sometimes deals, the reactions we choose, and the amazing things that can happen when we move step-by-step toward the things that make us come alive.

Growing up in Queens, New York, with an overbearing mother, Wolonick slowly realized the future her family envisioned for her didn’t match up with her own dreams. She moved across the country to California and got married, at first enjoying a newly adventurous life with her outdoorsy husband. But through the course of settling into family life, it became clear to Wolownick her husband was not the man she thought he was when they married. She struggled through years of loneliness, working as a writer and language professor, and trying to give her children the best life possible, all the while feeling like her own life was shrinking on her.

In The Sharp End of Life, released this week, Wolownick intermingles the stories of finding her own strength as a rock climber and distance runner later in life—inspired by her children, Alex and Stasia Honnold—with the stories of the fortitude and perseverance required to survive and try to thrive within what she calls a frustrating, isolating marriage. From her first day at the climbing gym at, at age 57, to crossing climbs off her Yosemite tick list—including Snake Dike on Half Dome only about a year later, followed by the likes of Matthes Crest and El Cap—we see Wolownick learning about herself as she seeks to better understand the outdoor world where her children thrive. We chatted with Wolownick to find out more about what it was like to begin climbing later in life, how she adapted to being “that boy’s mom,” and the impact climbing has had on her perception of herself.

Wolownick poses with her brother in front of the family brownstone in Manhattan, New York. Photo credit: Dierdre Wolownick collection.

You write about how much you felt your roles—as a wife, mom, teacher, writer, property manager—had defined your life, and I think many people can relate to that. How did running and climbing fit into that for you?

We are so tied down sometimes by what other people tell us we should or could do. Especially girls. Especially when I was growing up. It was a totally different world than now. I lived in a totally different type of social milieu—in an immigrant neighborhood after the war, with an Eastern European upbringing. So I had my roles. I was a girl. Girls could only be secretaries, or teachers, or nurses—that was it. And then they got married and some man took care of them. So roles were part of my life, but I never bought into them, to the great chagrin of my mother.

And as I got older, I had to buy into them. I was a teacher, and a mom, and I had to do the jobs required by those obligations. And I did. But in the back of my mind was my upbringing, saying, “You can’t do this, you can’t do that.” … But that changed little by little. I’d go jogging with the dog, and come back and tell Alex, “Yay, Alex, I just ran a mile!” And his take is different than most people’s take. He’d say, “That’s cool, Mom, if you can do a mile, you can do two.” And then, “Cool, Mom, If you can do two miles, you can do three.” And on and on it went. And that’s how I became a runner. Alex’s comments echoed what I felt, but that had been squashed by my life.

In one scene in the book, you go to the climbing gym on your own for the first time. You’ve tried it once with Alex and are curious to do more. You’re remembering how to put on your harness, and you know you need a partner, but are just a beginner. So you walk up to a stranger and offer a belay. For a first-timer, that took guts. What was that like?

It was very intimidating. I didn’t know anything, I didn’t know anybody. I knew I was lumpy and uncoordinated, but that I wanted to try it. You have to decide what you want, and what that requires. And if you’re not willing to do what it takes, you don’t want it badly enough. And I did want to try it, so I had to do that or go home—and I didn’t want to go home. It’s kind of like parenting, you do what you have to do and learn as you go.

At one point in the book, you describe years of loneliness in your marriage as being like a desert, and your new climbing friends like a refreshing rain. What was it about those relationships that felt so special?

It was the contrast—I had just survived 20 years in a dead marriage. My husband didn’t talk. He just didn’t talk. So I was alone with two kids forever. I hadn’t have any friends in West Sacramento because we’d just moved here. I was doing all these jobs, estate work, and working on houses. I had no social contact except at work. I didn’t have any time to myself, never had a minute to myself. And then I started climbing, and all of a sudden, I was hanging out with these wonderful people and spending whole days with them out at the crags, in the mountains or whole weeks or weekends with them, and it was like a desert bloom—like a superbloom, all of a sudden.

Friendships are often tied to where we are. When you’re at school, you make friends with people at school because you’re with those people every day. Or in a job, it’s the same deal. You make friends that way. But climbing is a lifestyle. It’s kind of all-encompassing. Everybody who climbs shares the same goals, tribulations, aches and pains, and techniques and everything. So there’s no age limit to it. Most of my friends are younger, though I have some older climbing friends, as well. It’s hard to do that in life in most other endeavors. We tend to gravitate toward the same age groups.

By nature of what we do, climbers have to be very dependable and reliable because there’s so much you have to be careful of, be aware of and understand. There’s physics involved, there’s knots involved, all kinds of things you have to know and apply, and do it perfectly or people could die. There are very few endeavors like that on the planet. If you go play basketball with your friends, and you don’t make the shot, you’re not going to die. But climbers have to have all those qualities or you’re all in danger. It’s a different kind of environment.

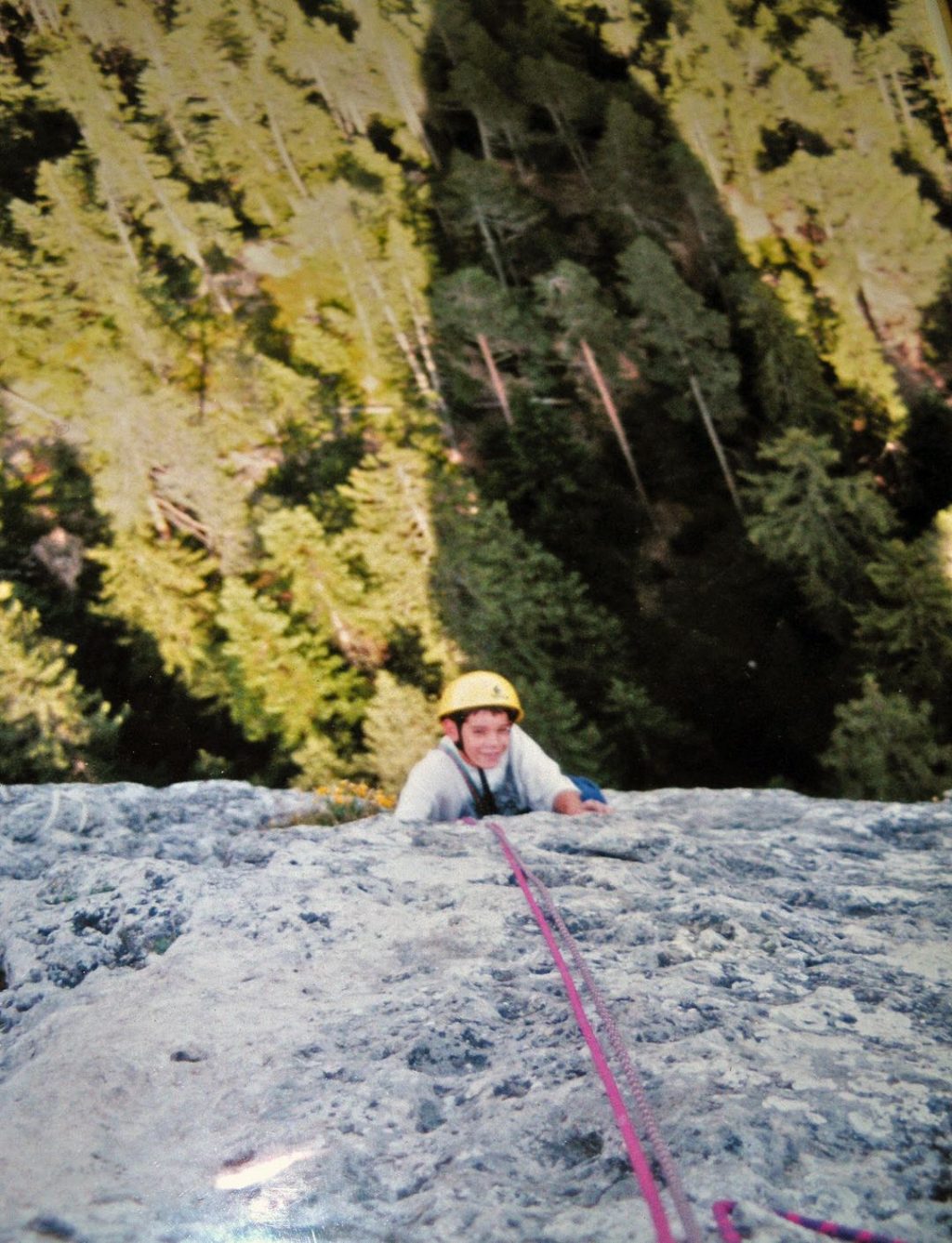

Alex Honnold on his first outdoor climb, at age 11. Photo credit: Philippe Poirier.

Through all of this, your son Alex is growing up to be a little different than most other kids on the playground, always moving and climbing—often to the frustration or worry of other parents. As he grows up you start seeing him featured in magazines, and decide to learn more about what exactly he’s doing, and you have to choose how you’re going to respond. What was it like to mother Alex Honnold?

The other adults were filled with advice for how to handle him. Because he was hard to handle. Other parents would have shut him down, given him drugs, or would have lost him. He would have left. People often told me to put him in gymnastics, or take him to a doctor to get him diagnosed—as if there was something wrong with him. I knew there was nothing wrong with him. He just loves to climb, and he loved something they didn’t love, so it was bad from their point of view.

But I could see he was a thoughtful kid, and within his own parameters he was very careful. He knew what he could do. We couldn’t do it, but he knew he could do it. And it drove the other adults crazy. They weren’t in control. So I had to relinquish a lot of control to raise him, and that’s hard for a lot of parents to do. With Alex, I had to trust his judgment. And I was just starting to when he was a kid. I had never seen anybody like this. All I knew was he was constantly on the go and always wanted to get higher, move up vertically on whatever presented itself. So I just had to change a lot of my preconceived notions and just be prepared to catch, just in case.

You write about never feeling like your parents took you seriously as an adult, that you felt they only ever saw you as a child. And yet with your own son, your roles have eventually flipped, with him taking you climbing and looking out for you. What was that process like?

It started taking place as soon as we started climbing together. Before that, when we were together, I was the adult in charge. I was mom. But when we went climbing together, from the very first time, I knew he knew what he was doing, and I didn’t. And that’s basically the situation children are in—they know the adults know how to pay for stuff, and do things and keep them safe. But now my son was doing all that—keeping me safe. He was telling me how to do what I needed to do. So it was a complete role reversal. And it was amazing—like, “Wow, that’s my son.” I was in awe, that he knows what he’s doing and does it better than me and I’d better listen to him and stay safe. It was wonderful to let go and just have him show me the ropes. I learn about technique and I learn about him. I learn from him every time we go climbing together. Especially on El Cap.

We all have to eventually learn to trust our children, for things like child care or house buying, as we age—this was that in spades. It was thrust upon me that I have to trust his judgment [when he’s climbing and free soloing] and I do, fully. But it doesn’t do away with the mom stuff, fully. That’s largely why I started to climb. I wanted to know what he’s up to out there.

Wolownick practices with her jumars on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Photo credit: Karalyn Aronow.

Through the course of your book, we see a huge shift in you—from being someone who feels trapped to being someone who sets goals and climbs routes that many climbers only dream about. How did you realize what you were capable of?

It was kind of an incremental process. It didn’t happen overnight. The first major climb I did with Alex was Half Dome. I had been climbing nine or 10 months by that point. But I was intrigued by these wonderful climbs that aren’t really, really hard, technically, in Yosemite. And I was making my tick list for someday. And Alex came home one day and said, “We should do Snake Dike on such and such day.” I was like, oh, you really think I can?

I wanted to—it was on my list. But it was on my list for someday. Like the way you put it on your list to someday go see the city of Rome. Someday. But Alex’s take is always the same, whenever I ask him if I can do this or that particular climb: Yeah, sure. Finally, I understand what he means by that: Yeah, sure, if you’re willing to do what it takes to learn what you need to know to go do that, and you want to do it badly enough, yeah, sure. So I started climbing my heart out at the gym, and that was the first one.

You write about how dying can take many forms, and living can also take many forms, and that recognizing that is one of life’s biggest challenges. Can you explain a bit more about what you mean by that?

A lot of people are not really living—they don’t think about it, and so they don’t do anything about it or acknowledge it. I grew up with a lot of people who just kind of existed and took up space. They never questioned anything. You have to question everything, and that’s how you grow. That’s how you become aware. And if you’re not aware, you’re really not living.

Choosing to live in an aware fashion, to make your own choices and not just let other people dictate what you’re allowed to do or should do—that’s the biggest first step. For decades, I wondered what was it like up there—what do they see when they go up El Cap, what does it take to get up there? I wondered that for years, but you keep wondering and delving, and who knows where it will go. That’s the exciting part of life.

Banner photo credit: Amy Mountjoy

Leave a Reply